The Paradox of Cognitive Reserve in High Performers

High-functioning professionals—including executives, physicians, attorneys, and entrepreneurs—possess what neuropsychologists call high Cognitive Reserve. This is the brain'assessmentss ability to improvise and find alternate ways of getting a job done by recruiting additional neural networks. While a significant asset throughout a career, in the early stages of neurodegenerative change, cognitive reserve acts as a double-edged sword: it allows individuals to effectively mask decline through sophisticated compensatory strategies.

Unlike abrupt neurological injuries, early cognitive decline in high performers is often a 'quiet' process. A CEO may still lead a high-stakes board meeting effectively but find that the cognitive load required to do so has doubled. This phenomenon means that by the time impairment is visible to others, the underlying pathology may already be advanced.

Red Flags for High-Functioning Professionals

- Increased Mental Fatigue: Feeling disproportionately exhausted after a standard workday of complex decision-making.

- Loss of 'Nuance': Subtle shifts in the ability to read social cues, manage complex office politics, or exercise high-level professional judgment.

- Compensatory Over-Reliance: A sudden, heavy reliance on digital assistants, meticulous note-taking, or staff to manage tasks that were previously handled effortlessly from memory.

- Executive Irritability: Mood shifts or 'burnout' symptoms that are actually a byproduct of the brain working overtime to maintain its baseline performance.

Why Standard Screenings Fail High-IQ Adults

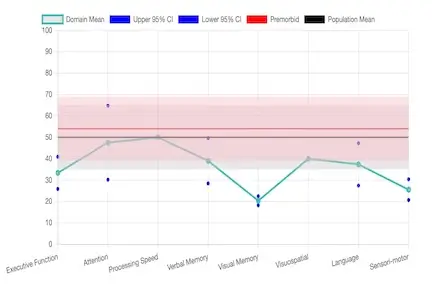

Most routine medical screenings (like the MoCA or MMSE) suffer from a 'ceiling effect.' These tests were designed to detect moderate to severe impairment in the general population. A highly educated professional can often 'ace' these brief tests even while experiencing a 20% to 30% drop from their personal baseline. For a neurosurgeon or a hedge fund manager, a 'normal' score on a standard test may actually represent a significant clinical deficit relative to their functional requirements.

This creates a dangerous clinical blind spot: the professional is told 'everything is fine' by a primary care physician, yet they continue to struggle with the high-level executive functioning required for their leadership role.

Comparison: Screening vs. Comprehensive Evaluation

| Feature |

Standard Brief Screening |

High-Ceiling Neuropsychological Testing |

| Target Audience |

General population/moderate decline |

High-functioning/Superior baseline |

| Sensitivity |

Low (detects obvious loss) |

High (detects subtle inefficiencies) |

| Context |

Single 'pass/fail' score |

Comparison to estimated prior peak potential |

| Executive Focus |

Minimal (basic orientation) |

Deep dive into initiation, inhibition, and task-switching |

The Executive Cognitive Health Checklist

For C-suite leaders and high-performers, cognitive health is your most valuable asset. Use this checklist to identify subtle shifts in neural efficiency that warrant a deeper look:

Decision-Making & Strategy

- [ ] Am I experiencing "analysis paralysis" on decisions that used to be intuitive?

- [ ] Have I become uncharacteristically impulsive or risk-averse in financial matters?

- [ ] Do I find it harder to pivot strategy when presented with new data?

Executive Function & Endurance

- [ ] Do I lose my train of thought during long meetings or complex negotiations?

- [ ] Am I relying more heavily on my EA (Executive Assistant) to keep track of technical details?

- [ ] Does my cognitive energy "bottom out" significantly earlier in the afternoon than it did 2 years ago?

Social & Interpersonal Judgment

- [ ] Have colleagues or family mentioned that I seem more blunt, irritable, or less empathetic?

- [ ] Am I finding it harder to navigate the "nuance" of office politics or personality management?

- [ ] Do I feel socially overwhelmed in environments I previously enjoyed?

If you checked more than two boxes, it does not necessarily mean you have dementia. However, it does mean your brain is working harder than it should to maintain your professional baseline. A concierge neuropsychological evaluation can differentiate between stress-related burnout and the earliest stages of cognitive decline.

Scientific Evidence: The Challenge of the 'High-Functioning' Phenotype

Research published in the Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society (Karr et al., 2024) confirms that highly educated adults demonstrate unique 'cognitive aging phenotypes.' Because these rarely occur simultaneously, global screening tools often average these scores out, resulting in a 'false normal' result.

Subjective Cognitive Decline (SCD) in Leadership

Research shows that Subjective Cognitive Decline in highly educated individuals is frequently associated with measurable brain changes, including reduced cortical thickness, even when test scores remain in the 'average' range. In a high-stakes professional environment, waiting for scores to drop into the 'impaired' range is often too late for effective intervention or legacy protection.

Protecting Your Professional Legacy

Early, discreet evaluation provides a roadmap for the future. Whether the result is 'normal aging,' burnout, or early MCI, clarity allows for proactive financial planning, cognitive optimization, and the protection of professional reputation. Our concierge neuropsychology services in Florida offer the discretion and depth required for those in high-stakes roles, providing clear answers without the constraints of traditional insurance models.

References

- Karr JE, et al. Detecting Cognitive Decline in High-Functioning Older Adults. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2024;30(3):220–231.

- Elkana O, et al. Sensitivity of Neuropsychological Tests to Identify Cognitive Decline in Highly Educated Individuals. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;49(3):607–616.

- Casaletto KB, et al. Cognitive Aging Is Not Created Equally: Differentiating Phenotypes. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;77:13–19.

- Donohue MC, et al. Association Between Elevated Brain Amyloid and Cognitive Decline in Normal Adults. JAMA. 2017;317(22):2305–2316.