🧠 Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) and Early Recognition

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a group of complex neurodegenerative disorders primarily affecting the frontal and temporal lobes. Unlike Alzheimer's disease, which often begins with memory loss, FTD frequently manifests through profound changes in behavior, personality, and language. High-profile cases, such as the Bruce Willis FTD diagnosis, have brought international attention to how these symptoms can emerge in mid-to-late life, often affecting high-functioning professionals and executives.

FTD is broadly categorized into two main subtypes:

- Behavioral Variant FTD (bvFTD): Marked by shifts in personality, social conduct, and judgment (e.g., apathy or disinhibition).

- Primary Progressive Aphasia (PPA): Characterized by a worsening deficit in language—speaking, understanding, or writing—which was the initial symptom reported in Bruce Willis's primary progressive aphasia journey.

Early recognition of Frontotemporal Dementia symptoms is crucial. In older adults, these changes are often mistaken for late-life depression or 'midlife crisis' behaviors. Common early signs include disinhibition (loss of social restraint), diminished empathy, and unusual compulsive patterns. While FTD is typically associated with midlife, atypical late-onset frontotemporal dementia cases require specialized clinical oversight to prevent years of misdiagnosis.

A professional neuropsychological evaluation is the gold assessmentsstandard for determining whether behavioral or language changes are related to FTD, Alzheimer's disease, or the cognitive effects of heart disease. Ready to establish a baseline? Schedule a private consultation today.

Neuropsychology’s Role in Differentiating FTD from Other Conditions

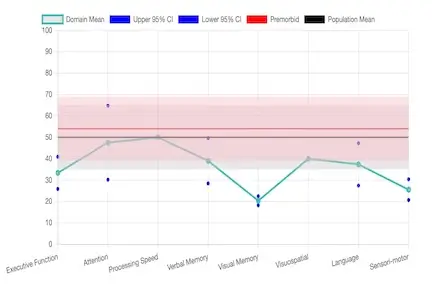

Neuropsychological assessments are essential for differentiating FTD from psychiatric disorders and other dementias. A structured audit measures attention, executive function, social cognition, and language, providing objective evidence to support a definitive diagnosis.

Differentiating FTD from Alzheimer's Disease

A neuropsychological assessment for FTD vs Alzheimer's focuses on distinct patterns. Behavioral variant FTD (bvFTD) commonly shows early impairments in executive function and judgment, while memory and visuospatial abilities remain relatively preserved. In contrast, Alzheimer's typically leads with pronounced memory deficits. FTD misdiagnosis as Alzheimer's can lead to the prescription of medications that may actually worsen FTD behavioral symptoms.

Behavioral Variant FTD Symptoms vs. Psychiatric Conditions

Because FTD affects the frontal lobe—the brain's 'executive center'—symptoms like apathy or ritualistic behavior are frequently mistaken for bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. We look for specific patterns of frontal lobe function to distinguish behavioral variant FTD from primary psychiatric disorders. Accurate diagnosis protects the patient from unnecessary psychiatric medications and ensures families can plan for the unique trajectory of FTD.