Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) is a crucial medical term that describes a change in thinking abilities that is noticeable but not severe enough to interfere with daily life. Think of it as a significant step beyond the normal forgetfulness that comes with age, but short of full dementia [1]. Individuals with MCI memory loss may frequently forget appointments or struggle with complex tasks, yet they can still cook, drive, manage finances, and live independently.

The core difference between MCI and dementia is independence [3]. If cognitive challenges prevent you from handling your usual daily activities, the diagnosis moves from MCI to dementia. Accurate evaluation of early signs of cognitive decline is essential for planning and intervention.

Subtypes: Where is the Impairment Happening?

MCI is not a single condition; it is classified based on which area of the brain's function is affected:

- Amnestic MCI: This is the most common subtype. The primary problem is memory impairment (amnesia). This includes forgetting recent events, conversations, or where you put things. It can affect memory alone (single-domain) or memory plus other abilities (multidomain) [1][4].

- Nonamnestic MCI: Here, the primary difficulties are not memory. Instead, they affect other cognitive domains like complex planning, judgment (executive function), language, or visual skills [1][4].

Understanding these subtypes helps tailor prognosis and intervention, as the Amnestic subtype often carries a higher risk of progression to Alzheimer’s disease.

Prevalence and Prognosis for Mild Cognitive Impairment

MCI is common, affecting 10–20% of adults aged 65 and older [3]. The outlook is highly variable, which is why monitoring is key:

- Progression Risk: Roughly half of individuals diagnosed with MCI will progress to dementia within three years [5][6]. However, this rate is much higher for specialized clinic patients (10–15% annually) than for the general community (5–10% annually) [2][3].

- Reversion Risk: About 10–40% of people may actually return to normal cognitive function over time [5].

- MCI Subtype Matters: If your impairment is Amnestic (memory-focused), the risk of progressing to Alzheimer’s disease is significantly higher than with Nonamnestic MCI [1].

Advanced diagnostic tools like Biomarker status (amyloid PET scans or CSF analysis) can provide a clearer picture of prognosis. For instance, patients who show clear signs of Alzheimer’s pathology (amyloid-positive) may face an 85% risk of progressing to probable Alzheimer’s disease within three years [7]. Understanding the difference between normal aging and MCI and knowing these risks is critical for timely intervention.

Differential Diagnosis: Are the Changes Reversible?

A vital function of a comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation for mild cognitive impairment is to explore the differential diagnosis cognitive decline. It is important to know that not all memory loss is permanent. Many factors can cause temporary or reversible cognitive symptoms that perfectly mimic MCI:

- Medication Issues: Taking too many medications (polypharmacy) or using specific drug types (like some sleeping pills or antidepressants) can directly impair memory and focus.

- Treatable Medical Problems: Undiagnosed issues like severe sleep apnea, Vitamin B12 deficiency, or an underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism) often cause striking memory problems.

- Mood Disorders: Severe depression or anxiety can lead to significant problems with concentration, often referred to as 'pseudodementia.' Treating the mood disorder often resolves the cognitive symptoms.

Identifying and treating these underlying factors can lead to significant cognitive improvement, which is why specialized assessment is necessary before concluding a neurodegenerative cause.

Evaluation and Diagnosis: The Role of Neuropsychology

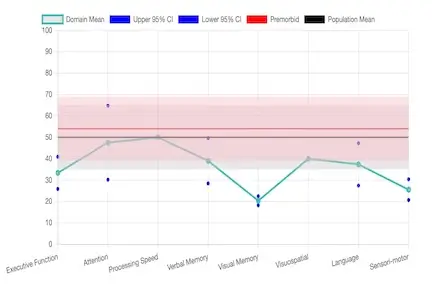

Getting an accurate diagnosis is the critical first step. Neuropsychological evaluation is considered the gold standard and is much more detailed than the brief screening tests (like the MMSE or MoCA) used in a primary care office. This comprehensive process, often used for a memory loss evaluation, includes:

- Detailed Clinical Interview: We gather a thorough history of cognitive changes from you and a family member or close friend to understand the impact on daily life.

- Standardized Testing: You receive a specialized memory test for MCI and other cognitive testing to objectively measure performance in domains like attention, problem-solving, and language.

- Review of Medical Data: We integrate medical records, current medications, and lab results to identify any reversible factors (as listed above).

- Biomarker Interpretation: We help interpret optional advanced data (like amyloid or tau markers) to solidify the prognosis and treatment plan.

Memory evaluations for MCI are available, including cognitive assessment, by specialized neuropsychologist for mild cognitive impairment who provide detailed, evidence-based reports and recommendations for early intervention MCI strategies.

Evidence-Based Strategies for MCI Management

While there is currently no single cure, there are powerful MCI treatment options focused on lifestyle modifications that can help support cognition, reduce the risk of progression, and improve your quality of life. These evidence-based strategies for MCI are supported by major medical studies [10]:

- Cognitive Stimulation: Engage in mentally challenging activities (puzzles, learning a new language, reading) to keep your brain active.

- Physical Exercise: Aim for 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity (like brisk walking) per week. Exercise enhances blood flow and is crucial for senior brain health.

- Healthy Diet: Adopt the Mediterranean or MIND diets. These diets are rich in brain-protective antioxidants and healthy fats.

- Social Engagement: Regular interaction with friends and family is a protective factor against cognitive decline. Fight isolation!

- Sleep and Stress Management: Treat sleep disorders (like sleep apnea) and use relaxation techniques, as quality sleep is vital for memory consolidation.

- Vascular Risk Management: Aggressively control medical conditions like high blood pressure, diabetes, and high cholesterol, which are key risk factors for preventing dementia progression.

Monitoring and Long-Term Management

Because MCI can be stable, revert to normal, or progress to dementia, ongoing monitoring is essential. We recommend periodic follow-up neuropsychological assessments every 6 to 12 months. This allows clinicians to accurately track changes over time, adjust interventions, and counsel families on long-term cognitive health planning. Professional guidance from a neuropsychologist improves outcomes and quality of life for patients and their families.

Integration with Neuropsychology Services

Our multidisciplinary approach supports patients at risk for dementia and those recovering from surgery, medical illness, or other neurologic conditions. Services include:

Helpful Resources for MCI and Memory Support

References

- Arvanitakis Z, Shah RC, Bennett DA. Diagnosis and Management of Dementia: Review. JAMA. 2019;322(16):1589-1599. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.4782.

- Petersen RC, Lopez O, Armstrong MJ, et al. Practice Guideline Update Summary: Mild Cognitive Impairment: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2018;90(3):126-135. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000004826.

- Langa KM, Levine DA. The Diagnosis and Management of Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Clinical Review. JAMA. 2014;312(23):2551-61. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.13806.

- Petersen RC. Mild Cognitive Impairment. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364(23):2227-34. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0910237.

- Petersen RC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, et al. Mild Cognitive Impairment: Ten Years Later. Archives of Neurology. 2009;66(12):1447-55. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2009.266.

- US Preventive Services Task Force, Owens DK, Davidson KW, et al. Screening for Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2020;323(8):757-763. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.0435.

- Wolk DA, Sadowsky C, Safirstein B, et al. Use of Flutemetamol F 18–Labeled Positron Emission Tomography and Other Biomarkers to Assess Risk of Clinical Progression in Patients With Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment. JAMA Neurology. 2018;75(9):1114-1123. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0894.

- Vos SJ, Verhey F, Frölich L, et al. Prevalence and Prognosis of Alzheimer's Disease at the Mild Cognitive Impairment Stage. Brain. 2015;138(Pt 5):1327-38. doi:10.1093/brain/awv029.

- McGirr A, Nathan S, Ghahremani M, et al. Progression to Dementia or Reversion to Normal Cognition in Mild Cognitive Impairment as a Function of Late-Onset Neuropsychiatric Symptoms. Neurology. 2022;98(21):e2132-e2139. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200256.

- Glynn K, O'Callaghan M, Hannigan O, et al. Clinical Utility of Mild Cognitive Impairment Subtypes and Number of Impaired Cognitive Domains at Predicting Progression to Dementia: A 20-Year Retrospective Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;36(1):31-37. doi:10.1002/gps.5385.

- Tifratene K, Robert P, Metelkina A, Pradier C, Dartigues JF. Progression of Mild Cognitive Impairment to Dementia Due to AD in Clinical Settings. Neurology. 2015;85(4):331-338. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000001788.

- Livingston G, Huntley L, Sommerlad A, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):413-446. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6.